The evolution of the classroom lecture

Olivia Wilkins

Catherine Drennan from MIT visited Caltech and met with students and faculty to discuss everything from her research in structural biology to her ideas about teaching pedagogy and general chemistry. During her visit, Dr. Drennan gave a talk called "Is the classroom lecture becoming extinct or simply evolving?" in which she discussed the "small changes [that] make a difference" in teaching, pulling from her own experiences teaching general chemistry. Throughout, she also showed the change in attitudes from students exposed to her classroom developments.

Dr. Drennan started by asking the audience to think of advantages and disadvantages of "traditional" classroom lectures. Here are some of the ideas for each:

-

- Advantages -

- The expert (faculty member) leads and maintains control

- Practical format for addressing a large group of people

-

- Disadvantages -

- Hard to engage with students

- Uncertainty as to whether students "get it"

- One lecture does not fit all (students at different levels in prior knowledge and have different disciplines/interests)

- The lecturer is the face of the entire field

Dr. Drennan then went into what she called "selective pressures", which were small changes she implemented in an attempt to evolve her classroom teaching. These included clickers, examples of application, and short videos.

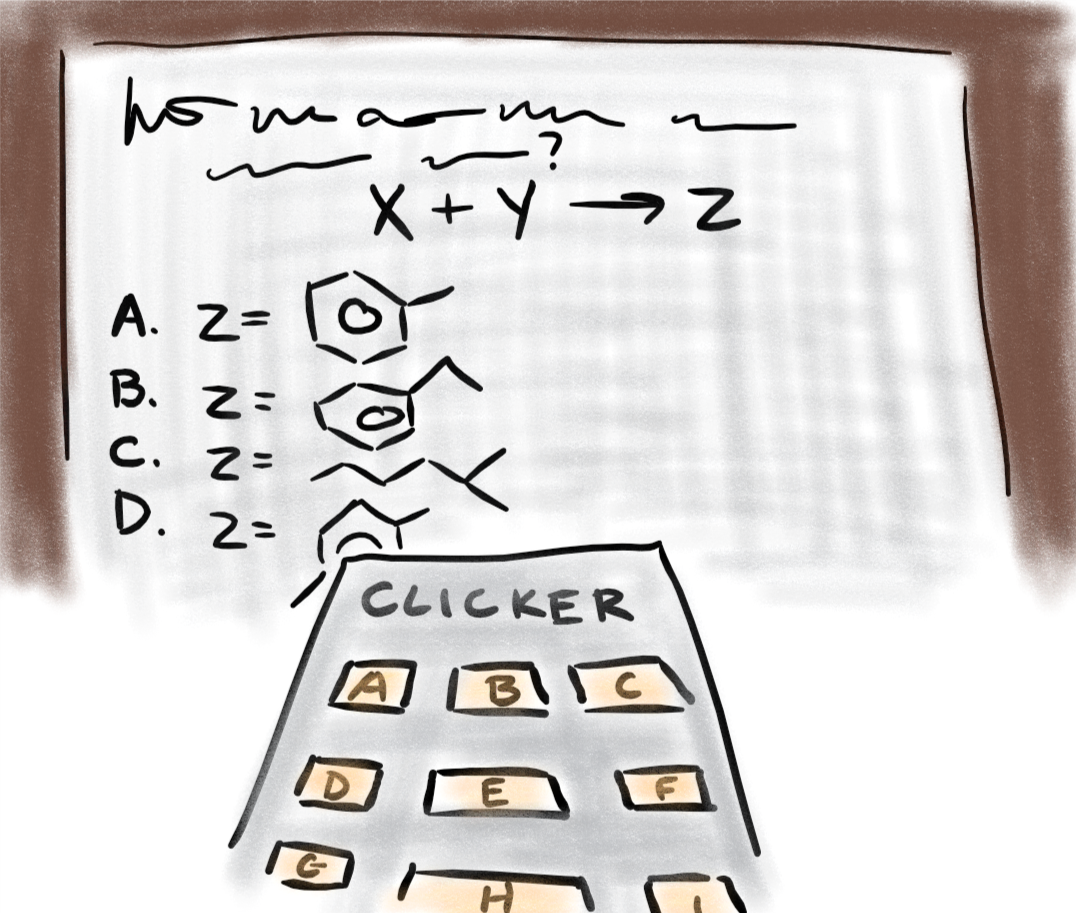

Clickers

Selective Pressure #1

The first small change discussed was how to use clickers in the classroom, emphasizing a key theme in teaching pedagogy: what technology you use is not important; it is how you use that technology that matters. Clickers are commonly used as a quick way to get instant feedback from your class. Pose a question, see if most people get it right, and decide whether to move on or try to explain confusing material in a new (and hopefully better) way.

Dr. Drennan proposed using clickers in a new way, describing what she called clicker competitions. In these competitions, teams of students separated by TA-led recitation section competed weekly to outdo other teams in clicker questions. Winning teams were rewarded with treats at the following week's recitation section, and some teams' TAs offered rewards to their group just for beating another (typically a friend's) team. The outcome was that students felt more engaged and challenged by the clicker questions, and overall they felt like their TAs wanted them to succeed more than had there been no competition. Whether students performed better in the class wasn't as clear, but attitudes overall improved.

Examples

Selective Pressure #2

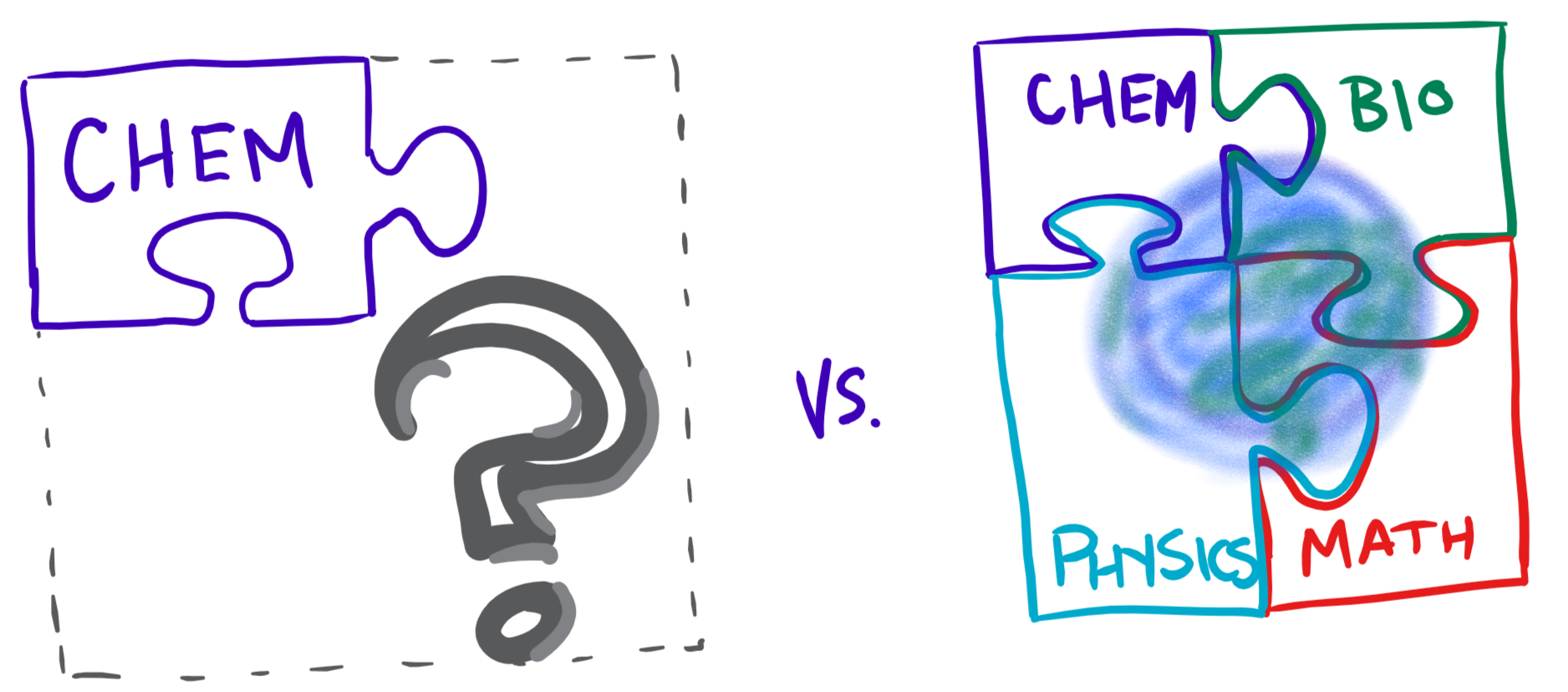

Dr. Drennan had looked at her pool of students and noted that most of them were not going into chemistry; the overwhelming majority of students in general chemitry were actually biology students (along with a significant number of engineers). Many admitted to not being interested in chemistry at all, and pure chemistry examples made chemistry seem like a dead science.

To combat these feelings, Dr. Drennan swapped out "pure chemistry" examples for real problems in biology and medicine. She also worded some problems to mimic tasks that might be expected of students doing summer research. As a result, students were convinced that chemistry was in fact useful, and they even became more interested in the subject. The actual content of the course did not change, just some of the practice problems. Thus students learned the basics of chemistry established decades and decades ago while understanding their utility in contemporary research fields.

Videos

Selective Pressure #3

I've been told that showing pictures of "old white guys next to their experiments" makes chemistry (and science generally) seem like a club that excludes women and people of color. The early pioneers of chemistry are (literally) the portraits of chemists, along with the lecturers who serve as living representatives of the field. That being said, students have little exposure to the breadth of people (i.e. everyone) who can become chemists. Even when others and their research are discussed in lecture, the portraits of what a chemist look like remain the same.

Dr. Drennan discussed a project in which chemists—from faculty to undergrads—developed two-minute videos showcasing MIT chemists from different research labs. (The videos can be viewed at chemvideos.mit.edu.) From these videos, students could see genuine excitement about chemistry and learn others' struggles, triumphs, and motivation for research. It is no surprise to me that students responded more positively to people who "looked like" them, but I was surprised by what "looks like me" meant for students. Dr. Drennan found that, regardless of gender and skin color, age was the characteristic most significant for whether students identified with a scientist or not.

To change the modern classroom, all it takes is some creativity to make small changes. Showing students that chemistry is collaborative, relevant to a variety of research fields, and most certainly not a dead science can foster appreciation for and interest in the discipline. There are many shortcomings to textbooks despite their potential to be great resources. Perhaps their biggest shortcoming is that they fail to show how real chemistry is. And unfortunately, these textbooks serve as the basis for many classroom lectures.

No, the classroom lecture is not dead, but only if it evolves to show that chemistry is something that any student can relate to.