ABCs of Course Design (1/3)

Olivia Wilkins

After two rounds of clashing schedules, I'm finally taking Dr. Jennifer Weaver's ABCs of Course Design. ABCs is a short-course that meets for three sessions to discuss designing a course using evidence-based teaching pedagogy and to give students a first run at designing a syllabus for a hypothetical (or real) course they'd teach in the next year or so. (Cam—my fellow grad student and co-teacher for Astrochemistry 101—are currently redesigning our tutorial course, so I'm using ABCs for a go at that.)

Throughout the course, Jenn will help us get a handle on things like backwards design, active learning, formative assessment, sumative assessent, motiviation, and learning outcomes, all while modeling best practices. After each installment, I'll share some key terms and points.

Jenn opened up the course by having us list the characteristics of a great course and the characteristics of a great teacher (i.e. things we should keep in mind when designing our own courses) in pairs before reporting back to the group. In addition to helping us think of characteristics we should strive for in our own classrooms, this exercise demonstrated a couple of things:

- Group work/activities can be done in lecture halls with stadium seating, not just at small tables.

- If you ask students to report back to the class after working in pairs only to be answered by the sound of crickets, you can ask students what their partner said. This can make students more comfortable with speaking up because they aren't being held directly accountable for their response.

- If you give students time to reflect on what you've talked about so far, they are more likely to retain that information. (This is another reason why I'm blogging about this.)

- The best time to stop students from discussing is just before they've run out of things to say. That way, students still have things to report back to the group, and they are still engaged in the material rather than talking about their weekend plans or checking their cell phones.

Student Development

In general, students move from a stage of dualism (where everything has a right and wrong answer and students just want to know what the answer is) toward (and sometimes, away from) a stage of commitment (wanting to reason why something is true). Between those are stages of multiplicity (knowledge can be subjective) and relativism (knowledge is contextual and relies on procedures). While your students may all be at different stages, it is important to remember they be at different stages for different topics or at different times. (If I didn't sleep well the night before, I certainly don't have the patience to reason why; I just want to know the answer sometimes!)

With that is the idea of the expert-novice continuum and expert amnesia. If we reach the development stage of commitment mentioned above, we've probably gotten to a place where we can connect all (or at least most) of the dots, making us experts who understand the big picture of a given subject. At that point, it can be difficult to remember that our students—novices—can't yet connect the dots. As teachers, we have to step back and try to help students make those connections, which requires us to remember how to make those connections ourselves. Not as easy as it sounds.

Backwards Design

"Backwards design" is a buzzword in the teaching community. It means to think first of the learning outcomes of the course and design lectures and assessments that will help students achieve those learning goals. (The opposite approach is to blindly give lectures and assessments without really thinking about what students will get out of it, but hoping they will take away something at the end of the course anyway.)

Backwards design is comprised of four steps: [1] Establish learning outcomes, [2] Assessment design, [3] Learning activities, and [4] Get results and improve.

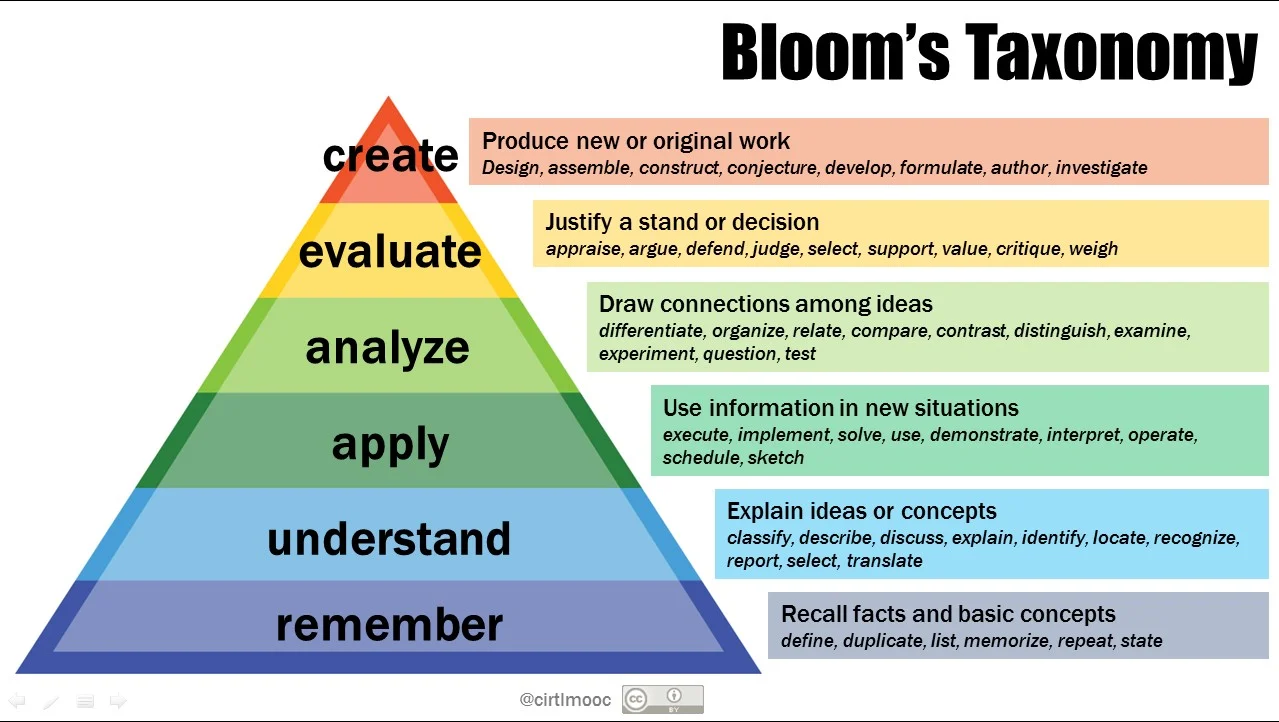

1. Establish learning outcomes (or goals or objectives). Learning outcomes are essentially a road map for students to know where they are going and what is required of them to get there. More bluntly, learning outcomes outline what knowledge and skills students should master. As a teacher, especially one excited about everything, you might think, my students should know everything, but this isn't realistic. Rather, you should think of a few key things that students should retain and designate the rest as being worth being familiar with, but non-essential; focus on the key things that students should retain first and go over the non-essentials if you have time. Ideally, your learning outcomes will be student-centered ("Students will be able to...") and incorporate action verbs from Bloom's Taxonomy.

2. Assess student learning. This involves coming up with a way to measure whether students "got it" and will ideally be useful for both the instructors and students to know how students are progressing through course material. Assessment should support students in developing understanding, rather than hinder or be disconnected from their progress.

3. Develop active learning activities. While there are some advantages to having a traditional classroom lecture, there are a whole heck of a lot of better ways to teach that allow you to quickly assess students' grasp on course content, engage with students, and adapt to students' needs. Active learning makes students actively engaged in course material rather than just passively absorbing it (or not). Such activities shoudl give students opportunities to revise, reflect, and refine their work based on feedback while practicing things like problem solving and experimentation.

4. Get results and improve. A good teacher revises their teaching to make it the best possible experience for their students. Getting feedback (not just giving feedback) is a key component of becoming a more effective teacher, and ideally you will get feedback throughout a course rather than just at the end of the course. While final feedback is great for future classes, it is even better if you can adapt your teaching for your current classes too.

In summary, the main ideas I took away from this week were:

- Great teaching is student-centered teaching.

- Design your course for what and how student should learn, not merely what you would like to teach them.

- Active learning activities and assessments should be made to fit the learning outcomes (not the other way around).