ABCs of Course Design (2/3)

Olivia Wilkins

In the first week of ABCs of Course Design, Dr. Jenn Weaver taught the class about group work, student development, and backwards design and cemented the idea that great teaching is student-centered teaching. In the second week of ABCs, Jenn brought these topics back in while focusing on strategies for motivating your students, teaching transparently, and implementing active learning.

Motivating Your Students

Jenn opened week 2 with reminding us that one goal in teaching is helping students move from a stage of dualism (at which they just want to know what the answer is) to a stage of commitment (at which they want to reason why something is true). Students' motivation to get there is based on value to them, belief they can succeed, and cues in the environment (e.g. supportive messages from teachers). The value piece includes both intrinsic and extrinsic value. While extrinsic value typically takes the forms of final grades, intrinsic value consists of students' sense of mastery of a subject and understanding of how to apply a subject to their own interests or to real-world tasks. Students' belief they can succeed is based on their understanding of their own capabilities as well as an understanding that their actions are related to outcomes. While this is strongly rooted in previous expereiences, cues in the environment have major impact on students' confidence in their ability as well as how much they want to work toward mastery in a given subject. Environmental cues can be direct—like complimenting students on a job well done, giving words of encouragement in doing better, or explicitly stating criteria for success—or more subtle—like using inclusive language (e.g. using students' gender pronouns rather than assuming them, acknowledging what students' diverse backgrounds can bring to the class that a homogeneous group could not) and avoiding language like "As you already know..." or "Obviously...". Ultimately, if students feel welcome in a classroom, they will be more motivated and confident to succeed and will probably place higher value on that material.

In practice, motivating students can be done in a variety of ways (based on How Learning Works, compiled by Jenn Weaver), such as:

- connecting material to students' interests

- providing authentic, real-world tasks

- showing relevance to students' lives and careers

- showing passion and the value you place on learning (nothing is de-motivating quite like a teacher bored by their own subject!)

- identifying an appropriate level of challenge

- articulating expectations

- providing early success opportunities (not just a final exam)

- providing rubrics

- describing effective study strategies

- getting personal ("I would approach this by...")

All of this can be done by...

Teaching Transparently

Transparency in teaching can be applied to both assignments and the course overall as well as to in-class activities. In both cases, transparent teaching requires first setting forth a purpose: skills that will be practices, content knowledge that will be gained, and possible applications. This is followed by a process or task and clearly explaining what students' will do and how they will do it. (Explaining how students will complete a task is

Often, these elements are already present for each assignment, but they might be kept inside a teacher's head rather than be shared directly with students. Teaching transparently means you don't assume, for instance, that a good essay does not follow the 5-paragraph format taught in high school; for students with less writing background or a weaker foundation in writing assignments, you can help by taking 10 seconds to add a line to an assignment prompt stating this. If you have types of sources you expect students to cite in mind, express that! In different classes and disciplines, these expectations might be different, so flat-out saying what should be included in your assignment will help your students and save you from a lot of frustration. (To be transparent, you should also have assignment prompts in the first place!)

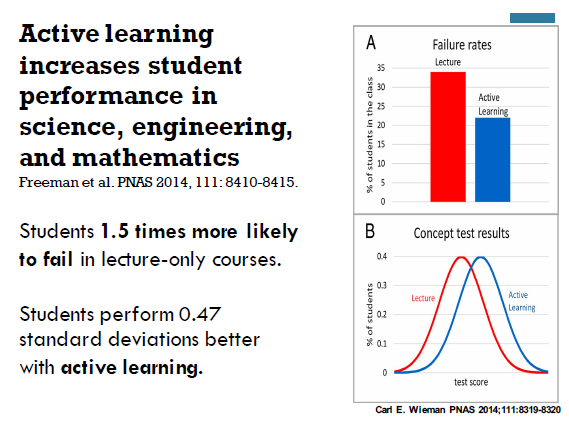

Active Learning

To many, "active learning" sounds like applying a flipped classroom style to your teaching or lecturing for 10 minutes and facilitating 50 minutes of group activities. While these are certainly examples of active learning, they fall on the extreme end. Active learning is any activity or strategy that causes students to engage with material rather than just passively recieve it from lecture. While it requires at least a little more work on the instructor's end, the benefits have been shown to be well worth those efforts.

Slide from Jenn Weaver's ABCs of Course Design; references noted therein

Active learning, as we learned in Jenn's ABCs, doesn't require a complete overhaul of your class. (Jenn encourages you start small and gradually incorporate more and more active learning into your classroom over time, especially if you have never tried your hand at active learning in the past.) Active learning can take the form of reflective writing (e.g. "muddiest point", minute papers, 5-minute reviews) that guage what students took away from a topic you covered and identify difficult concepts reported by students; Think/Write-Pair-Share (students take a minute to think of a response to a prompt, talk it over with a neighbor, and report back to the whole class) which guages what students understand, engages students with peer-to-peer interactions (while making them commit to an answer), make use of peer feedback, and get students to speak in class (perhaps by reporting what their neighbor said to take the pressure off themselves); classroom response systems such as clickers, Plickers, Poll Everywhere, or hand signals that provide feedback to you (and your students) via formative assessment as well as keep track of participation/attendance; pair/group work using lapboards or problem solving at the board that guage what students understand, go beyond the multiple-choice style of aforementioned response systems, and utilize group work and discussion; and flipped classrooms in which students are introduced to new material outside of class and work together with peers and instructors in class on higher levels of learning (applying, analyzing, evaluating, creating levels of Bloom's Taxonomy).

There are numerous benefits to incorporating active learning, but there are challenges, such as time, motivating students to buy into the activities, and assessing whether an activity will actually facilitate learning. With practice and careful planning, however, active learning can transform a lecture into a more fruitful learning experience for your students!

In summary, the main ideas I took away from this week were:

- students are motivated when they see value in what they are learning and when they feel they are capable of being successful,

- transparent teaching requires making (oftentimes) small adjustments to be more clear about your expectations, and

- even the smallest activities in class can have big impacts for how well students engage material.